When Origin Stories Collide

How my search for my family’s roots intersected with the Cherokee Nation — and The 1619 Project

Earlier this month, on an episode of the PBS program “Finding Your Roots,” Angela Davis, the 1960s activist and social justice icon, learned that one of her forebears came to America on the Mayflower:

This segment of the series, hosted by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, underscores a unique aspect of the Black American experience: our collective inability to know our complete heritage.

While most in the Black diaspora will never be featured on PBS, a by-product of the technological revolution is the democratization of information. As a result, anyone with a smartphone or an internet connection can access census information, birth, and death certificates, and even marriage licenses going back hundreds of years.

Family legacy is as much a part of popular culture as it is a part of our history. In the HBO series Game of Thrones and its spin-off, House of Dragons, the importance of family is central to a broader theme. The families featured in both series are identified by a sigil, a coat of arms imbued with mystical qualities. Sigils symbolize the family heritage and its power, or the lack thereof.

An ancient book detailing the lineages of each house is a foundational component of both epic sagas. Most Americans of European descent quickly identify with George R.R. Martin’s tale.

But for Black Americans, the show’s portrayal of the family dynamic is a fantasy. Historically, attempts to determine our origin stories only go back a few generations and usually end at America’s eastern shore.

For example, my last name, Weems, is a Scottish variant of the Scottish Wemyss. My mother’s maiden name, Muldrow, is an Anglicized version of the ancient Irish surname Muldrew. Since no one in my family has been within a thousand miles of Ireland or Scotland, neither of these surnames accurately reflects my family history.

In my case, as with millions of Black Americans, both names are remnants of a past that America would rather we forget. They are the lingering symbols of possession placed on my forebears by the white Americans who enslaved them.

Thanks to companies like 23andMe or Ancestry, anyone with a smartphone or an internet connection can access census records, birth and death certificates, and even marriage licenses going back hundreds of years if you’re willing to provide your DNA. A few years ago, I decided to do just that.

What followed was a journey that began in North Carolina and ended in the Cherokee Nation.

The WEOC Book Club

Last year, I wrote about the events leading up to the Trail of Tears. My interest in this aspect of American history stemmed in part from participating in a book club last year, hosted by Writers and Editors of Color (WEOC), a collective of writers representing the diverse spectrum of people of color.

The book on our agenda was The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. One of the chapters that piqued my interest was entitled Dispossession, an essay on the connection between indigenous tribes and chattel slavery.

As I read about how the leadership of the indigenous peoples immersed themselves in Anglo-European traditions, including the enslavement of Africans, one person’s name practically jumped off the page. The name was John Ross. Here’s what I wrote about Ross in my piece on The Trail of Tears:

Under the Cherokee Nation’s matrilineal system of the 17th and 18th centuries, children of mixed ethnicity born to a Cherokee mother became part of her family and clan. Cherokee children also derived their social status from their mothers.

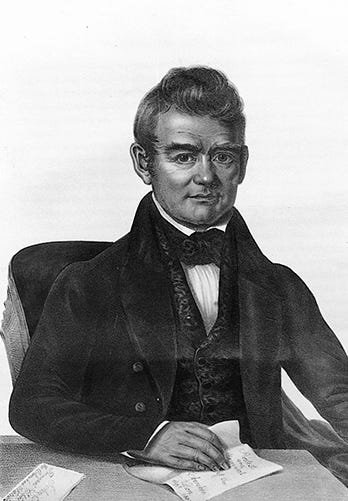

John Ross, the leader of the Cherokee Nation from 1828 to 1866, was only one-eighth Cherokee by blood. Born to a Scottish father and a mother who was part Cherokee, the blue-eyed, fair-skinned Ross identified as Cherokee while receiving an education in white institutions. Because Ross was bilingual, he was the perfect go-between in Cherokee negotiations with the U.S. government. And as was the case with the wealthy elite across the Civilized Tribes, Ross was an enslaver.

Ross, the son of a Cherokee mother and Scottish father, was the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation for nearly forty years. Despite his fair-skinned appearance, he identified as indigenous. Interestingly, the literal translation of Guwisguwi, his tribal name, means “Mysterious Little White Bird.”

Although Ross was acculturated in Cherokee traditions, he was also fluent in British colonial society and attended learning institutions specifically for mixed-race Cherokee children. Because the bilingual Ross led the relocation known as the Trail of Tears, he is often described as the “Moses of the Cherokee People.”

But the chapter in The 1619 Project was not the first time I’d encountered John Ross’s name. The first time was when I searched for my own family’s origin story.

The Search for My Roots

For Father’s Day in 2019, my family gave me a subscription to Ancestry.com and AncestryDNA. Despite my initial misgivings regarding privacy, I sent Ancestry a DNA sample, hoping to uncover my complete family history. A few weeks later, I received my results. The assessment of my lineage was a little surprising.

According to Ancestry, my “ethnicity inheritance” is a smattering of various African ethnicities. The highest percentage of my DNA was 10% Nigerian, next were Sweden and Denmark, which combined to equal 8%. I even had a small percentage of Scottish DNA.

I started my genealogical search on my wife’s side of our family tree. Since she is of European descent, the process only took minutes. Once I plugged information for my wife’s parents and grandparents into Ancestry’s app, the trademark “leaves,” representing clues to one’s lineage, instantly populated with centuries of information.

The trip down my genealogical rabbit hole took a lot more work. Unlike the families of A Game of Thrones, I had no sigils, no coats of arms, and no books tracing the lineage of my ancestors to rely upon.

As with most American descendants of enslaved Africans, my knowledge of my family’s history came from word-of-mouth accounts and only went back a few generations. After scanning dozens of census, birth, and death records on Ancestry, I traced my family’s history back to Samuel Arnold, an enslaved ancestor born around 1798 in North Carolina. Ironically, this is where I reside today.

In Alabama in 1824, Samuel Arnold and Matilda, his thirteen-year-old wife, had a daughter named Ariann. Census records list Ariann’s race as Mulatto, or half Black and half white. Her story is murky, but after disappearing for several years, she resurfaces a few decades later. In the Cherokee Nation.

A biracial female matching Arrian’s approximate age and description appears on the Slave Schedule of the 1860 census for the Tahlequah District of the Cherokee Nation, which shows a tally of enslaved men, women, and young children.

There are even categories for enslaved runaways and the mentally damaged. The first time I saw one of these schedules, these anonymous records of enslaved human beings, it brought me to tears.

Because the enslaved on the schedule are not identified by name (only race, gender, and age), I can’t be 100% certain, but it appears that Ariann was sold to the Cherokee Nation.

One of the two owners listed on the Slave Schedule is John Ross, Cherokee Chief — the same man whose name I encountered months later while reading The 1619 Project. It seems that the man known as “the Moses of the Cherokee Nation” may have enslaved one of my distant ancestors. Adding to the mystery of my origin story is this: in 1865, Ariann had a son. His name? John C. Ross.

Did Ariann travel the Trail of Tears? Did she bear a child with John Ross? Is that what accounts for my smidgen of Scottish DNA? Like most descendants of enslaved Africans, my questions will probably remain unanswered.

Unanswered, that is, unless I’m fortunate enough to appear on Henry Louis Gates’ PBS program.

If you enjoy and want to support my writing, please consider signing up as a paid subscriber. You’ll receive early access to all my posts and subscriber-only podcast. You’ll also get invited to occasional Zoom events and paid-subscriber-only chats.

@the eggcademic (she/her/她) thanks for sharing!