The Plutocracy’s Achilles’ Heel?

Citigroup’s infamous strategy for exploiting wealth inequality also provides a roadmap for how to defeat it

Although I’ve been away from Wall Street for more than a decade, I still talk to many of my former colleagues, some almost daily. Many are former competitors, others worked with me on one of the trading businesses I ran.

Beyond our years of friendship, they are my direct line to the business. Aside from keeping me posted on the latest scuttlebutt, topics of conversation of late have centered around the uncertainty of our times, the societal changes, and, of course, the economy.

Sooner or later, our discussions touch on the dramatic wealth accumulation by those at the top of the food chain, especially the plundering of wealth since the onset of the pandemic.

Every now and then, one of my former partners in crime brings up Citigroup's research on wealth inequality which, while roundly criticized at the time for its tone-deafness, has eerily predicted our current circumstances.

Two years ago, I wrote an essay that focused on one of the bank’s notorious research notes. Actually, the investment bank issued three pieces of research on the topic between 2005 and 2006, all of which focused on exploiting the rise in global income inequality.

To my mind, the research is some of the most offensively arrogant content published by a Wall Street bank. That said, the unique nature of this moment in time calls for a revisitation of Citigroup's plutonomy thesis.

Citigroup’s researchers popularized plutonomy, a mashup of plutocracy and economy.

According to the company’s trilogy, “economic growth is powered by and largely consumed by the wealthy few.” Here is their overall thesis (emphasis added):

What are the common drivers of Plutonomy? Disruptive technology-driven productivity gains, creative financial innovation, capitalist-friendly cooperative governments, an international dimension of immigrants and overseas conquests invigorating wealth creation, the rule of law, and patenting inventions. Often these wealth waves involve great complexity, exploited best by the rich and educated of the time.

We project that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) will likely see even more income inequality, disproportionately feeding off a further rise in the profit share in their economies, capitalist-friendly governments, more technology-driven productivity, and globalization.

In a plutonomy, there is no such animal as “the U.S. consumer” or “the UK consumer,” or indeed the “Russian consumer.” There are rich consumers, few in number, but disproportionate in the gigantic slice of income and consumption they take. There are the rest, the “non-rich,” the multitudinous many, but only accounting for surprisingly small bites of the national pie.

When Citigroup’s October 2005 note, Plutonomy: Buying Luxury, Explaining Global Imbalances, crossed my trading desk, even my uber-capitalistic traders were stunned by its political incorrectness. None of us could believe the investment bank said the quiet part so loudly or with so much enthusiasm.

It is important to keep in mind that the target audience for Citigroup’s trio of plutonomy research notes was the bank’s ultra-wealthy clientele and not the 90% of the global population they intended to exploit.

What I find most interesting about Citigroup’s hypothesis isn’t their full-throated argument on behalf of naked avarice, but rather the circumstances the bank's analysts saw as the risks to the strategy's success.

I’ve concluded that for those who, like myself, happen not to be ultra-wealthy, what Citigroup saw as risk factors to their strategy are in fact, a partial roadmap for triumphing over the plutocracy and, thus, wealth inequality.

For example, relegated to page 24 of the 30-page report was a risk factor that, should it come to pass, threw a monkey wrench into the investment bank’s entire inequality exploitation scheme:

Low-end developed market labor might not have much economic power, but it does have equal voting power with the rich … if voters feel they cannot participate, they are more likely to divide up the wealth pie rather than aspire to being truly rich.

Put another way, should the working class ever wise up to the “you too can be rich if you just work hard enough” con, they may become pissed off enough to begin voting in their own interests.

In Citigroup’s March 2006 Revisiting the Plutonomy: The Rich Getting Richer, the firm’s analysts give themselves a collective pat on the back for accurately predicting the continued wealth accumulation by the top percentile and the increase in wealth inequality.

Still, in a brief section entitled “Risks: What can go wrong?” they again warn that the elite’s global money grab may end should “the non-rich” recognize their superior numbers and begin voting like it. Once again, Citigroup says the quiet part out loud:

Our whole plutonomy thesis is based on the idea that the rich will keep getting richer. This thesis is not without its risks. For example, a policy error leading to asset deflation, would likely damage plutonomy.

Furthermore, the rising wealth gap between the rich and poor will probably at some point lead to a political backlash. Whilst the rich are getting a greater share of the wealth, and the poor a lesser share, political enfrachisement remains as was – one person, one vote (in the plutonomies). At some point it is likely that labor will fight back against the rising profit share of the rich and there will be a political backlash against the rising wealth of the rich…We don’t see this happening yet, though there are signs of rising political tensions.

Citigroup’s third report on the strategy, The Plutonomy Symposium — Rising Tides Lifting Yachts, went a few steps further in enumerating the risks to their exploitative strategy:

[W]e see four primary risks. The first, war and/or inflation. Secondly, financial collapse. Three, the end of the technological revolution. Finally, political pressure to end the increase in income and wealth inequality…

As much of the wealth of the plutonomists is held in one shape or other in financial wealth (as opposed to land or property), the state of the financial system is important. Financial collapse, as in the Great Depression in the US, would be a serious challenge to the plutonomists…

…Perhaps the most immediate challenge to Plutonomy comes from the political process. Ultimately, the rise in income and wealth inequality to some extent is an economic disenfranchisement of the masses to the benefit of the few. However in democracies this is rarely tolerated forever.

Citigroup’s last note turned out to be remarkably prescient because August of the following year marked the beginning of the worst financial collapse since the Great Depression — a Black Swan event that should've upended the bank’s investment strategy. And yet, rather than suffer the devastation Citigroup predicted, the opposite occurred, according to the Harvard Business Review:

When house prices collapsed in 2008, the value of middle-class households’ portfolios dropped substantially, while the quick rebound in stock markets boosted wealth at the top. Due to their heavy investment in equities, the top 10% wealthiest households were the main beneficiary from the stock market boom while being at the same time relatively less affected by the drop in residential real estate prices. The consequence of substantial wealth losses at the bottom and in the middle of the distribution coupled with wealth gains at the top produced the largest spike in wealth inequality in postwar American history.

So while Citigroup’s analysts were spot on regarding the extent to which the financial crisis would drag the country into the economic gutter, even they underestimated the government’s commitment to bailing out Wall Street.

In the aftermath of the crisis, we became a nation of renters as nearly 10 million homeowners lost their primary source of wealth to foreclosure. A 2018 study found more renters than homeowners in cities with populations over 150,000.

Was the ‘pandemic pillage’ the last straw?

In many ways, the Covid-19 pandemic was a wake-up call for the masses. Mandatory lockdowns forced us to watch in real-time as the system’s inherent unfairness played out. It caused many to reevaluate how they value the labor they provide. Income and wealth inequality, once a conversation relegated to academia, was suddenly brought to the forefront of conversations.

As with the financial crisis, the government went to great lengths to save Wall Street by shoveling dollars into the financial system. Indeed, there is an argument that by pumping almost $5 trillion into the financial markets to keep Wall Street afloat, the Fed is, at least in part, responsible for sparking today’s runaway inflation.

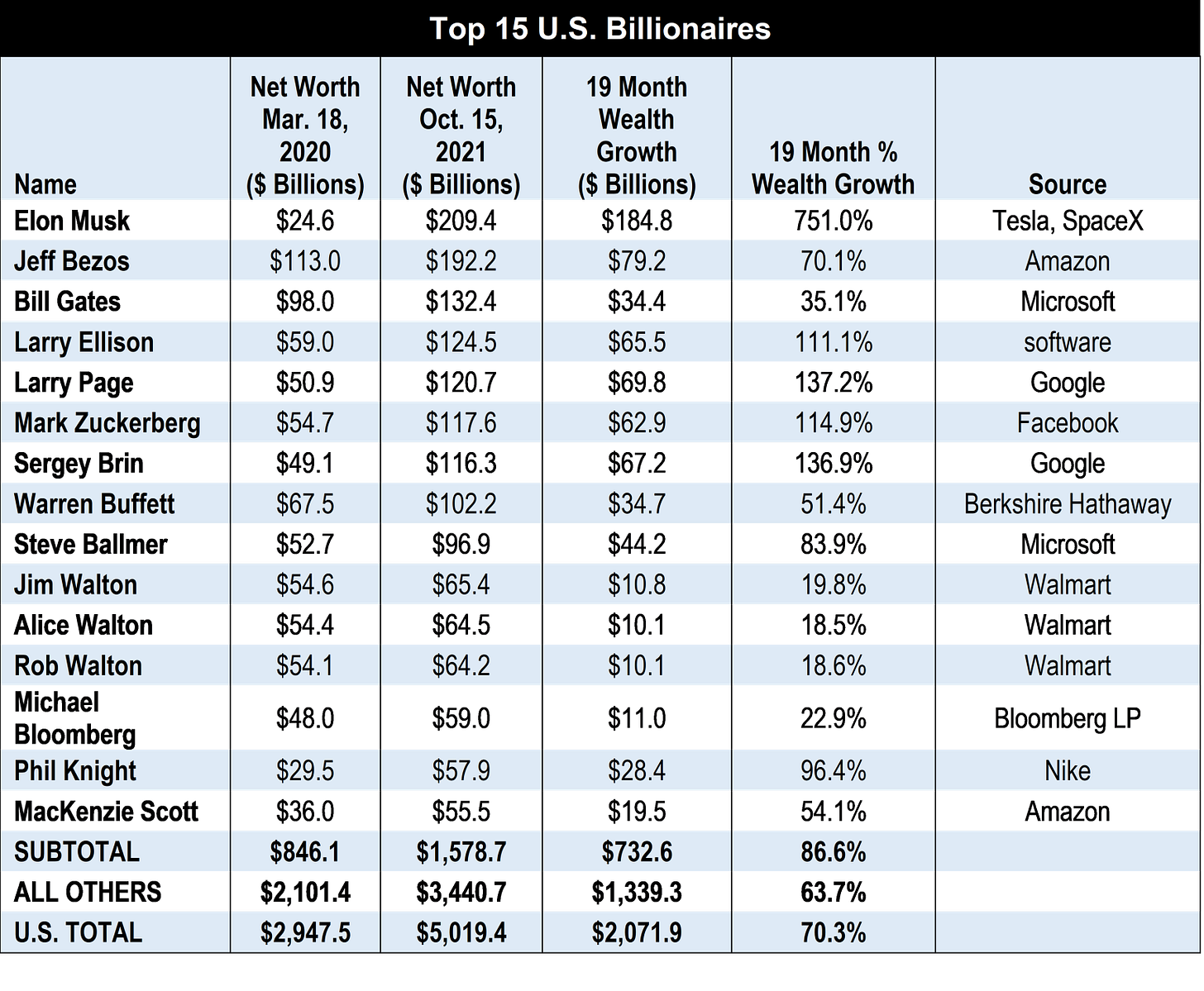

While the pandemic ravaged the country, the billionaire class took the opportunity to plunder the economy. For example, at the start of the pandemic, Elon Musk had just under $25 billion in wealth. As of May 4 of this year, Musk’s wealth had increased tenfold, to more than $250 billion.

The Institute for Policy Studies had this to say regarding the exponential growth of U.S. billionaire wealth during the pandemic:

This troubling juxtaposition underscores the story of unequal loss and sacrifice during the worst pandemic in a century. While billionaires have seen their wealth surge, millions have lost their lives and livelihoods...

On March 18, 2020, at the beginning of the formal lockdown, U.S. billionaires held a combined $2.947 trillion. On May 4, 2022, as the U.S. crossed the 1 million death mark, according to an analysis by NBC, 727 U.S. billionaires were worth $1.71 trillion more, according to Forbes.

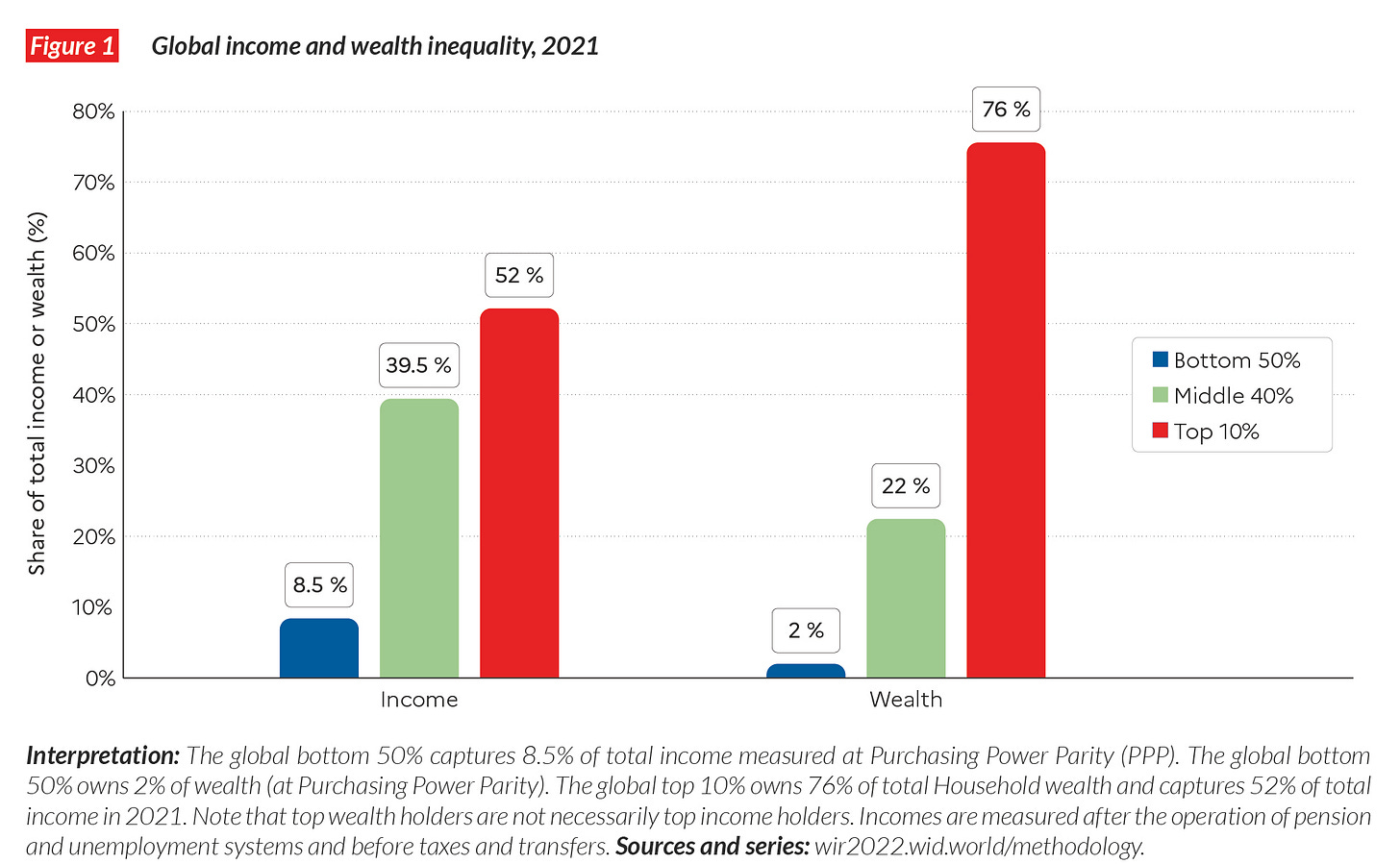

With the poorest half of the global population barely possessing any assets to speak of and the moneyed few owning more than 75% of all the wealth on the planet, where do we go from here?

Perhaps we’ve reached an inflection point, where those who labor will begin to exercise their hidden power by voting, just as Citigroup predicted almost two decades ago.