The Plutocracy Always Wins

As the saying goes, if you're wondering who the sucker is, it's you.

In 1956, Elvis Presley released a tune entitled Hound Dog, one of his most famous songs. The song was one of the first to sell 3 million copies and even made it into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Elvis Presley wasn't the first singer to record Hound Dog. That honor goes to Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, a Black singer who recorded the song three years before Elvis. Her version went to #1 on the R&B charts and sold 500,000 copies. It was her biggest hit. She made a royalty of $500.

Although Elvis's version of the song wasn't the first, it's the one everyone remembers.

Just before the start of the Great Recession, a group of Citigroup research analysts issued a series of reports advocating a controversial strategy, picking up on a trend that had been around for dozens of years. Their strategy: how best to use the stock market to exploit the trend of rising income inequality.

Like Elvis, Citigroup's analysts weren't the first to notice the trend. Still, they certainly popularized the idea – perhaps because no one previously dared to put such a vile proposition in print. When the research note crossed the trading desk I managed at the time, reactions ranged from “Is this a joke?” to “Are they f*cking serious?”

The idea was not a joke, and the strategy was dead serious.

Plutocracy + Economy = The 1%

The series of Citigroup research reports introduced a new word to the investment lexicon — Plutonomy — a portmanteau for plutocracy and economy. Citigroup spent years downplaying, if not suppressing, The Plutonomy Memos, as they've come to be known.

You won't find a download of these reports on the company's website. Search the internet long enough, and you may find a few posts from bloggers online, but the posts don't stay up for long — thanks to Citigroup lawyers.

Given the investment strategy the memos champion, it's easy to understand why. Here are a few excerpts outlining the general thesis of Plutonomy: Buying Luxury, Explaining Global Imbalances, issued in October 2005:

“The World is dividing into two blocs — the Plutonomy and the rest. The U.S., UK, and Canada are the key Plutonomies — economies powered by the wealthy.”

“We will posit that…the world is dividing into two blocs — the plutonomies, where economic growth is powered by and largely consumed by the wealthy few, and the rest…Often these wealth waves involve great complexity, exploited best by the rich and educated of the time.”

The note then estimates specific areas of increased inequality:

“We project that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) will likely see even more income inequality, disproportionately feeding off a further rise in the profit share in their economies, capitalist-friendly governments, more technology-driven productivity, and globalization.”

And for the money shot, Citigroup's analysts warned investors that voting was the most significant risk to the continued concentration of wealth:

“Low-end developed market labor might not have much economic power, but it does have equal voting power with the rich…Perhaps one reason that societies allow plutonomy, is because enough of the electorate believe they have a chance of becoming a Pluto- participant. Why kill it off, if you can join it? In a sense this is the embodiment of the “American dream”. But if voters feel they cannot participate, they are more likely to divide up the wealth pie, rather than aspire to being truly rich.”

And so, as if the general public needed another reason to hate Wall Street, Citigroup popularized the 'inequality trade,' a series of investment recommendations specifically intended to exploit the chasm between the super-wealthy and everybody else.

While Citigroup downplayed the report, rising inequality — especially in the US — made the “plutonomy trade” a safe, if not morally bankrupt, bet. That changed recently as Democrats and a few Republicans voiced support for policies such as prison reform, limits on buybacks, universal healthcare, and climate initiatives that address inequality.

By 2019, Ajay Kapur, the analyst who coined the word 'Plutonomy,' lamented that perhaps his signature strategy was no longer a sure thing.

Stock market euphoria vs. the edge of dystopia

I've been asked how the stock market can set records during such awful economic conditions. Even though the market seems divorced from reality, there are several reasons causing the deviation from the norm.

First of all, a divergence between the stock market and the real economy isn't unusual. The markets are forward-looking, unlike the way we typically view the real economy. That's why economic reports usually reflect activity from the prior week, month, or quarter.

The stock market rises or falls based on the prospects of individual companies. On the other hand, statistics such as GDP and unemployment reflect the country's overall health. So there's always a divergence between market perception and economic reality because the metrics aren't the same.

The Federal Reserve's fiscal stimulus activities could be the reason for the dramatic rise. Short-term interest rates are nearly 0%, and interest on Treasury bonds is below the rate of inflation. This is part of the Fed's strategy to prop up big businesses — and Wall Street — with massive amounts of liquidity to keep them afloat through the pandemic.

A side effect of the Federal Reserve's actions is that the stock market becomes the investment of last resort. Traders call the situation a TINA, which is shorthand for There Is No Alternative.

Zero for you, billions for the 1%

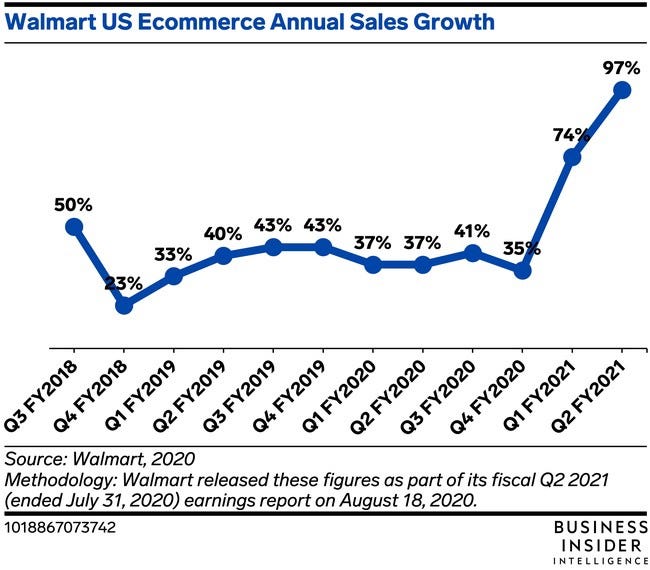

There is a direct through-line from the market-driven success of Tesla, Facebook, Amazon, Walmart, and Google to the obscene wealth of the American oligarchs that own the majority of stock in each company.

While the American commoner class frets over paying bills, their children's education, or making next month's rent, there's a huge celebration happening. Unfortunately for most Americans, the fete is at a venue most cannot afford — the stock market.

The stock market is on an absolute tear. Since the 30% collapse in March of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, it — along with the Nasdaq and the S&P 500 — are on a streak, setting one record high after another.

Sadly, most Americans won't participate in this enormous display of wealth creation. At a time when going shopping in person or hugging a friend could cost you your life, the rich still manage to keep getting richer.

This month alone, Apple became the first $2 trillion company, and Target's second-quarter profits surged 80%. Walmart's e-commerce sales were up 97%. It's incredible what a sequestered customer base does for the bottom line.

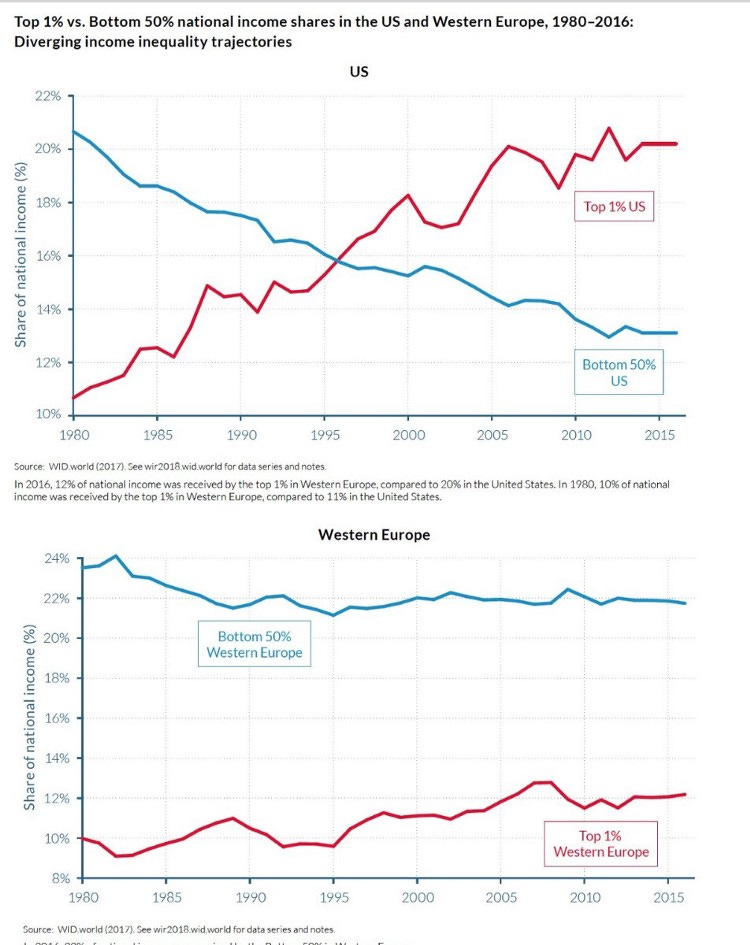

Even before the pandemic, the bottom 90% of wage earners owned only a fragment of the stock market. In the first quarter of this year, the top 10% own nearly 90%. With millions of newly unemployed, that statistic is probably worse in recent months.

Despite the country's economic collapse, it's a great time to be a billionaire. While regular folks hang on for dear life, things for the billionaire class couldn't be better.

In 1982, the list of Americans who made the first Forbes 400 list of the nation's wealthiest owned .93% of the country's wealth. As of August 2020, for the first time in history, the top 12 wealthiest billionaires — owners of Walmart, Google, Amazon, et al. — had a combined wealth of over $1 trillion. In July of this year, Jeff Bezos, Amazon's CEO, saw his net worth increase by $13 billion in a single day.

But as the markets and the one-tenth-of-one-percenters popped the proverbial champagne, in the last two weeks, over $2 million more people filed for unemployment benefits.

For the country's billionaire class to amass record levels of wealth while the country as a whole experiences dramatic economic decline is not only grotesque — it's emblematic of everything wrong with how American capitalism works for the average citizen.

The good news is that, with this level of inequality, the Plutonomy trade is still intact. Somewhere, Ajay Kapur is smiling.