The Other Hamilton

Jeremiah G. Hamilton may have been America's first Black millionaire, but the Wall Street broker was no role model.

In 1983, there were only three Black financial services professionals in the entire state of Arkansas. I was one of them. A decade later, I started the first Black-owned investment bank in Arkansas. For a little more than a decade, I was part of an exclusive club — the world of Blacks on Wall Street.

For more than thirty years, I navigated the universe of Black-owned investment firms, ultimately building and managing a successful program trading operation for one of the largest minority-owned investment banks on Wall Street. Most people are unaware of this, but there is a rich history of Black entrepreneurs in finance going back decades. Indeed, my journey through the world of finance was made possible, at least in part, by the blood, sweat, and tears of Black trailblazers that came years before me.

These iconic figures are part of a unique historical tapestry. They include Travers Bell, who co-founded Daniels & Bell, the first Black-owned investment bank on the New York Stock Exchange in 1971; Wardell Lazard, who left Salomon Brothers in 1985 to start WR Lazard & Co., and Carla Harris, who rose through the ranks to become a Vice Chairman at Morgan Stanley, one of the world’s largest investment banks. But those modern-day trailblazers were not the first Blacks to excel on Wall Street.

A few years after Alexander Hamilton lost his duel with Aaron Burr in Weehawken, New Jersey, another Hamilton, Jeremiah G. Hamilton, was born in Haiti — or perhaps Virginia. He claimed both places as his birthplace, so we may never know for sure. At the time of his death in 1875, Hamilton was purportedly the wealthiest Black man in the United States. Believed to be America’s first Black millionaire, he amassed a fortune worth $2 million, the equivalent of $50 million today.

The existence of a super-rich Black financier excelling on 19th century Wall Street at the height of slavery, seems about as unlikely as the color-blind world of Shonda Rhimes’s Bridgerton, especially since there is so little physical evidence to mark Hamilton’s existence. Fortunately, two sources of information, newspapers, and court records, document many of Hamilton’s exploits.

So who was Jeremiah G. Hamilton?

By all accounts, he was a ruthless businessman. In an era when Wall Street was indeed an unregulated casino, Hamilton gained his wealth through real estate speculation and insurance fraud, using bankruptcy to shield his assets whenever his schemes fell through.

While ethics seem to play no role in his investment decisions, by Wall Street standards at the time, Hamilton was hardly an outlier.

Hamilton first came to prominence in 1828 as the mastermind of a bold counterfeit coin scheme. Representing a group of prominent New York merchants, the 21-year-old Hamilton ran the illicit coins from Canada through New York and ultimately to Haiti.

But the deal went south, forcing Hamilton to flee Haiti after hiding out for 12 days in Port-au-Prince harbor under the protection of local anglers. Haitian authorities confiscated the Ann Eliza Jane, a ship chartered by Hamilton. They sentenced him in absentia to be shot for the crime of counterfeiting, an offense punishable in Haiti at the time by death.

A decade later, Hamilton engaged in a profiteering scheme after New York City’s Great Fire of 1835, pocketing nearly $5 million in today’s dollars. He later capitalized on New York’s real estate boom, purchasing 47 properties in present-day Astoria and several docks, piers, and parcels of land in upstate Poughkeepsie.

Hamilton was such an audacious player in 19th-century finance he even dared to take on shipping and railroad magnate Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, vying for control of Nicaragua’s Accessory Transit Company. Even “The Commodore,” as Vanderbilt was known, came to respect Hamilton as a worthy adversary.

The day after his death in 1877, the National Republican ran Vanderbilt’s obituary on its front page, noting: “There was only one man who ever fought the Commodore to the end, and that was Jeremiah Hamilton.” Interestingly, though the newspaper acknowledged Hamilton by name, it omitted that he was Black.

But while he was a success on Wall Street, ironically, Hamilton’s Black contemporaries did not consider him a hero. In an 1852 letter to Frederick Douglass, Black intellectual James McCune Smith criticized Hamilton for what he perceived as Hamilton’s unseemly pursuit of wealth.

It seems the disdain was mutual. Hamilton avoided relationships with Blacks in favor of whites. He did not contribute to Black causes and even ignored racial taboos of the day by marrying Eliza Jane Morris, a white teenager nearly half his age. By all accounts, Hamilton was unmoved by the plight of the enslaved, focused only on enriching himself.

According to Eric Herschthal of The Daily Beast, in the 1830s, Hamilton purchased $2.5 million worth of sugar and coffee — produced on the backs of enslaved Africans in Cuba. In general, Black leaders viewed Hamilton’s financial scheming and insensitivity to the Black community as shameful. After Hamilton gained notoriety for his Haitian counterfeiting scheme, the country’s first Black newspaper, New York’s Freedom’s Journal, rooted for Hamilton’s capture. Herschthal noted:

Many Black citizens saw Haiti — established by former slaves in 1804 — as a beacon of promise, its hoped-for success a way to refute the notion of Black inferiority. That Hamilton sought to defraud the country was no small insult. In 1852, Frederick Douglass’s newspaper published a series of essays on whether becoming wealthy would dispel prejudice against Blacks. James McCune Smith, a leading Black intellectual, took the opportunity to make a swipe at Hamilton: “Compare Sam Ward” — an admired black antislavery activist — “with the only black millionaire in New York, I mean Jerry Hamilton; and it is plain that manhood is a ‘nobler idea’ than money.”

How did Hamilton become so successful during a period in which Black people were considered only three-fifths of a man? Ironically, wealthy white New Yorkers were more interested in the color of Hamilton’s money than that of his skin. In the 1860s, Hamilton managed an “investment pool” similar to the hedge funds of today. Whatever their racist feelings towards him, white investors eagerly gave Hamilton complete discretion over the pool’s investments.

Potential investors were so enthusiastic about investing with Hamilton, that many provided him with gifts to increase their chances of gaining access to his investment pool. Hamilton reportedly encouraged one would-be investor to “send him a basket of champagne and a box of segars” for entry into his investment pool.

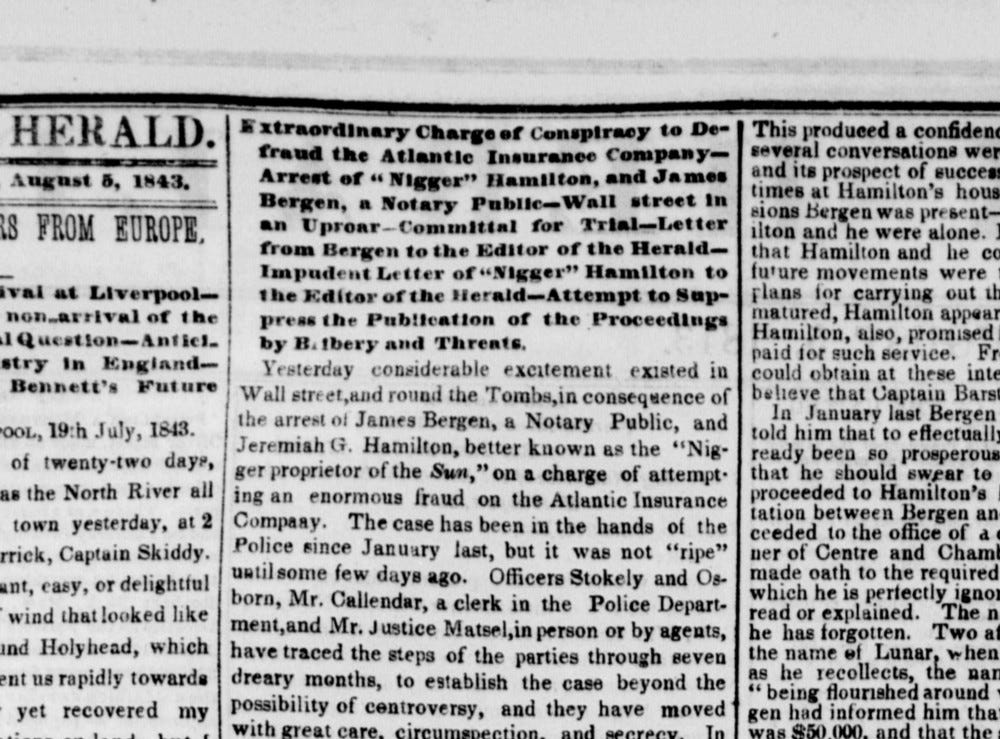

But despite all his monetary success, Hamilton could not escape racism. Newspapers of the day referred to him using the more disparaging moniker, “Nigger Hamilton.” His Wall Street contemporaries despised his exploits and his character, branding him with the nickname “The Prince of Darkness.” Away from Wall Street, Hamilton was just another Black man in pre-Civil War America. During the New York Draft Riots of 1863, white mobs turned on New York’s Black citizens. According to Shane white, author of Prince of Darkness: The Untold Story of Jeremiah G. Hamilton, Wall Street’s First Black Millionaire, city archives show that rioters deliberately targeted Hamilton’s home.

Nevertheless, Hamilton challenged America’s pre-Civil War conventions regarding race and the place of Blacks in American society. A larger-than-life figure on Wall Street for at least 40 years, he excelled in an arena that still struggles today with racial inclusion. Hamilton was a lone Black man on a lily-white playing field, defying our common perception of pre-Civil War New York City.

Long before Madam C.J. Walker, the country’s first female self-made millionaire — of any race — made her fortune in Black hair care, Hamilton was a fixture on Wall Street. Unlike Black entrepreneurs that became successful at marketing goods and services to Black consumers, Hamilton accumulated his fortune as a shrewd financial dealmaker. Yet, he is essentially an unknown figure.

Hamilton left no papers behind after his death and there are no known portraits of him, adding to the mystery of the obscure Black broker. But though he may be an obscure figure in the annals of Black history, he may yet have the last laugh. In 2017, actor Don Cheadle acquired the film and television rights to White’s Prince of Darkness. Soon, the world may learn Hamilton’s story, compliments of Hollywood.