The Coup Attempt That Didn’t Fail

The Wilmington Massacre of 1898, America's only successful coup d'état, has eery parallels to the January 6 attack on the Capital

On January 6, 2021, a mob of Donald Trump’s supporters, consisting mostly of white nationalist militias, military personnel, and even members of law enforcement, attacked the U.S. Capitol in an armed insurrection. The objective of the rioters was to stop the peaceful transfer of power.

As the world watched in on live television, the predominantly white crowd ransacked the seat of American democracy. Violent rioters beat police with flags, while others waved the Confederate flag in the Capitol rotunda, an act that had never occurred previously — not even during the Civil War.

Hours later, with the country still reeling from the attempt to overthrow the government, a majority of the House Republican caucus voted to overturn the results of the Electoral College vote. Even in the Senate, 147 Republican senators joined in the baseless effort to nullify the confirmation of the Biden-Harris ticket. At its core, the Jan. 6 insurrection and the Republican votes to decertify the Biden-Harris election victory was a failed coup attempt.

But while the effort to overturn the 2020 election was a shock to the system, it failed. The only successful coup in America’s history occurred in the waning days of Reconstruction when white supremacists succeeded in overthrowing a city’s lawfully elected government.

The Wilmington Coup

On November 10, 1898, white supremacist Democrats staged a violent attack by an armed mob of roughly 2,000 white men in Wilmington, North Carolina. Led by the city’s light infantry and a band of vigilantes armed with rifles and a Gatling gun, their objective was to remove the city’s elected Fusionist government to install white supremacist Democratic Party members.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” ~Mark Twain, American author and humorist

The mob forced the city’s elected leaders out of office at gunpoint, demolished local businesses, and destroyed the property of Wilmington’s Black citizens, including The Wilmington Daily Record, the city’s Black-owned newspaper.

According to the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report by the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission, the exact number of deaths from the attack is unknown, but at least 60 African Americans were killed. Hundreds of Blacks fled the city, leaving their homes and businesses, hiding in nearby woods or swamps in fear for their lives. Although no whites died during the massacre, local and national media falsely portrayed the incident as a “race riot” perpetrated by Blacks.

Leading up to the coup, Democratic congressman W. W. Kitchin, warned, “Before we allow the Negroes to control this state as they do now, we will kill enough of them that there will not be enough left to bury them.”

During the Reconstruction Era, there were numerous incidents of white supremacist violence targeting newly freed Blacks. However, historians believe the Wilmington Coup of 1898 (sometimes referred to as the Wilmington Massacre of 1898 or the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898) is the only incident of its kind in U.S. history.

Most historians view the massacre as the nation’s only successful overthrow of an elected government. For that reason, historians and experts have characterized the insurrection as America’s only coup d’état .

The Wilmington Coup also has a particular distinction due to the coordination of white supremacists and the Democratic Party. Then, as in the 2020 election, a political party used misinformation and white grievance to incite a violent uprising.

Wilmington: A Black Mecca

In the 50 years following the Civil War, society in Wilmington had achieved near post-racial status. The University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s Dr. W. T. Schmid wrote of live in Wilmington during the years leading up to the massacre:

“African Americans enjoyed considerable progress from 1865–1898. Black literacy in North Carolina rose dramatically from virtual total illiteracy to 2/3 that of whites. Black literacy in Wilmington was the highest in the state. African Americans worked as skilled craftsmen along the riverfront, owned businesses, and held positions in local government (firemen, police, city officials). Wilmington was regarded as a “Black Mecca” by some — a fact that some white working men resented and white business leaders saw as dangerous. Some blacks owned considerable property, including Thomas Miller, a pawnbroker, and real estate owner.”

The majority-Black port city was the largest municipality in the state.In 1890, while Blacks comprised only 25% of the state’s population, they accounted for nearly 80 percent of Wilmington’s 20,000 inhabitants, according to the Wilmington Race Riot Commission.

The formerly enslaved migrated en masse to the town, resulting in increased economic opportunities. African Americans held positions in every segment of Wilmington’s workforce, from laborers and industrial workers to skilled artisans, government employees, and professionals.

Blacks also held numerous elected positions in Wilmington. and were prominent within the community, unlike many of the state’s other jurisdictions. According to Schmid, by 1887, four of the city’s ten aldermen and thirteen of their thirty policemen were Black. Blacks served as the justice of the peace, deputy clerk of court, street superintendent, coroners, police officers, mail clerks, and mail carriers.

While many formerly enslaved Wilmingtonians initially used their skills in service positions (nearly 35% became bakers, grocers, etc.), after 1889, many Blacks migrated to other areas of employment due to higher demand and wages. Two African American brothers, Alexander and Frank Manly, owned The Wilmington Daily Record, Wilmington’s only Black-owned newspaper.

The Fusion Movement

Unlike the Tulsa “Black Wall Street” Massacre in 1921, which began when a white woman accused a Black teen of assault, the attack on Wilmington was the result of years of planning.

As with the January 6 insurrection, politicians played a pivotal role in the Wilmington Coup. White supremacist Democrats and their allies’ strategy to re-take Wilmington’s government depended on a combination of stoking white grievances and calls for law and order.

In the 1890s, the Fusion movement manifested itself in North Carolina and several other southern states. The movement was a national phenomenon of the 1890s in which different political parties formed alliances due to shared interests.

The coalition was particularly successful in North Carolina, where the Populist Party and the state’s predominantly Black Republican Party formed a Fusionist coalition. The political and economic success of the Fusionist coalition of Black Republicans, and white farmers upset the long-standing domination of Democrats in Wilmington and throughout the state.

In the years preceding the assault on Wilmington’s government, the North Carolina Fusionists won every statewide election, winning the governorship in 1896 and Wilmington’s municipal election in the following year.

The most important political leaders in Wilmington and surrounding area were John Campbell Dancy, the Customs Officer of the Port of Wilmington, and Congressmen George P. White (both Black Republicans) and Silas B. Wright, the city’s first elected mayor.

In striking similarity to the 2020 election, the Fusionists won a legally contested election. In 1897, the North Carolina Supreme Court decided in favor of the Fusionist ticket. The result in Wilmington was a new municipal government consisting of four Blacks out of the city’s ten aldermen and 13 Black officers out of the city’s 30 policemen.

The new social order drove resentment among Democrats, many of whom had sided with the Confederacy and owned slaves before the war. The power dynamic of African Americans holding positions of authority served to raise racial tensions.

The White Supremacy Campaign of 1898

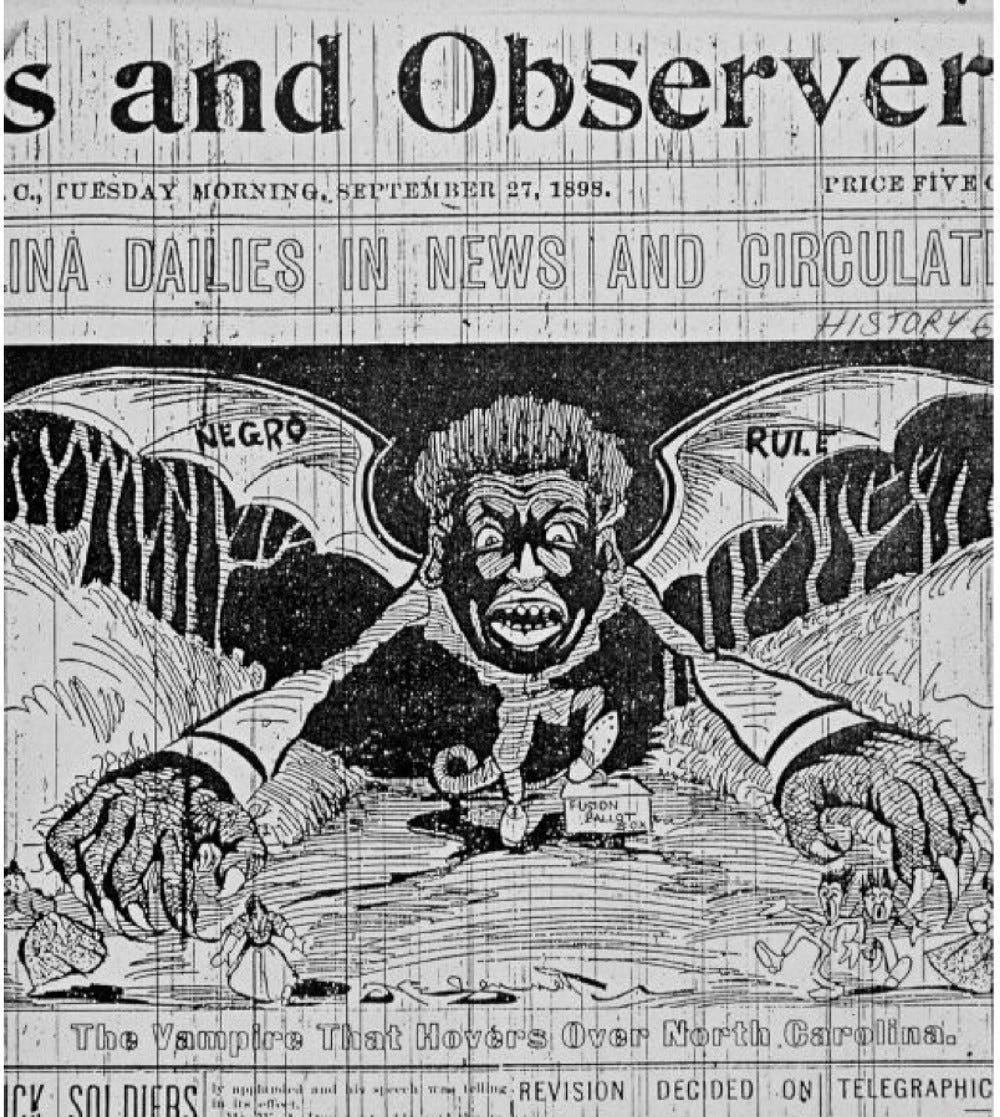

In late 1897, nine prominent Wilmington men, known as “The Secret Nine,” began a conspiracy to re-take government control and put an end to what they referred to as “Negro Rule.” Democratic State Party Chairman Furnifold Simmons focused the Party’s 1898 campaign strategy on one issue — white supremacy. Simmons recruited sympathetic media outlets to assist with the Democratic disinformation strategy, such as The News & Observer, The Charlotte Observer, The Caucasian, and The Progressive Farmer.

During the 1898 election campaign, Democratic Party-aligned newspapers portrayed Blacks as insolent, disrespectful of whites in public, and corrupt, also making claims of Black men’s unwelcomed interest in white women. Simmons accused the white Fusionists allied with Black Republicans of supporting “Negro domination” and a breakdown of law and order. According to the Cape Fear Museum of History and Science, Democrats issued a statewide call for white unity:

“North Carolina Democrats looked for a unifying issue to organize around during the 1898 election season. And they chose to rally around the idea of white supremacy. This idea took hold in 1897: “Immediately following a key meeting of the Democratic Executive committee on 20 November 1897, the first statewide call for white unity was issued…it called upon all whites to unite and ‘reestablish Angle Saxon rule and honest government in North Carolina.’”

In late 1898, prominent North Carolina Democrats organized the white Government Union, whose constitution called for “the supremacy of the white race.”

In the days leading up to the 1898 election, the Red Shirts, a terrorist paramilitary unit of the Democratic Party, patrolled every street in Wilmington. They disrupted services in Black churches, fired gunshots into Black-owned homes, and warned Blacks not to vote. Democratic congressman W. W. Kitchin warned, “Before we allow the Negroes to control this state as they do now, we will kill enough of them that there will not be enough left to bury them.”

The day before the election, the leaders of the conspiracy gathered a thousand white Wilmingtonians in Thalian Hall to declare their intention to remove the city’s elected municipal government:

Four hundred and fifty-four men then signed the “The White Declaration of Independence,” which proclaimed that the framers of the U.S. Constitution had never anticipated “the enfranchisement of an ignorant population of African origin” and “that the men of the State of North Carolina who joined the Union did not contemplate for their descendants a subjection to an inferior race.” They went on to declare that “we will no longer be ruled, and will never again be ruled, by men of African origin.”

On Election Day, armed Red Shirts gathered outside Wilmington polling places, threatening any Blacks who attempted to vote. In the end, the strategy succeeded; Democrats won every elected position for which they ran. But Wilmington’s Fusionist government held on to power, and the city’s municipal election was not until the following year. Two days after the state election, hundreds of white men rode into the town, burning homes and destroying businesses.

Neither state nor federal leaders intervened in response to the violence in Wilmington. North Carolina’s Republican governor did not request federal assistance, so President McKinley did not send troops to quell the attack. In the aftermath, the U.S. Attorney General’s Office U.S. launched an investigation in 1900, but no one involved in the massacre was ever indicted.

The Wilmington Coup was a watershed event in post-Reconstruction Era politics, and served as a springboard for the restrictive Jim Crow laws that followed. In 1900, North Carolina Democrats passed an amendment--still in the state’s constitution today--requiring voters to pass a literacy test. By 1908, every state in the South adopted similar changes to their respective constitutions specifically intended to disenfranchise Black voters.

Describing the ramifications of the incident in Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy, author Laura Edwards wrote, “What happened in Wilmington became an affirmation of white supremacy not just in that one city, but in the South and the nation as a whole.”

White supremacist Democrats in North Carolina and across the South viewed the Wilmington incident as confirmation that “whiteness” superseded a Black American’s rights of citizenship and individual rights, not to mention the equal protections guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The immediate consequence of the Wilmington Coup was the mass exodus of many African Americans from the city. According to Schmid, as many as 300 Blacks fled in the days following the massacre. Over the next year, the once-majority Black population evaporated, with 14 percent of the Black citizenry leaving the city. By 1900, whites held a majority in Wilmington.

The 1898 Wilmington massacre marked the end of Black political power in the South for decades. The massacre served as a precursor to Jim Crow, the white supremacist caste system that would persist throughout the South for the next six decades.

Wilmington Today

Today, Wilmington is no longer the largest city in the state, falling behind Charlotte and Raleigh. The Black majority never returned to its peak in the 1890s. One hundred years later, African Americans comprised about 20 percent of New Hanover County’s inhabitants. By 2019, only about 13 percent of Wilmingtonians identified as Black.

Modern-day Wilmington bills itself as a family-friendly destination for retirees, with racial diversity noticeably absent from its pitch to would-be tourists. To its credit, the Port City acknowledges the 1898 massacre and its racist past — to a degree.

For years, the North Carolina Azalea Festival was marketed as a celebration of the town’s Southern heritage, featuring Southern belles dressed in hoop skirts reminiscent of the antebellum era.

Thanks to the racial reckoning of 2020, the Cape Fear Garden Club, which oversaw the Azalea Festival’s Antebellum-era program, announced its cancellation. And last summer New Hanover County Commissioners voted to rename the park named after Secret Nine member Hugh MacRae.

In the decades since the Wilmington Coup, newspapers, and history, portrayed the deliberate attack by white supremacists as patriots confronting corrupt and unruly Blacks. Sadly, North Carolina’s current political leaders seem determined to bury the state’s history again, at least as it relates to white supremacy and racism.

This month, the state’s Republican-led House passed House Bill 324, a bill barring public schools from teaching that America “is racist or sexist or was created by members of a particular race or sex to oppress members of another race or sex.”

Similarly, due to pressure from conservative activists on its board of trustees, the University of North Carolina recently rescinded its offer of tenure to Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist — and alumnus — Nikole Hannah-Jones due to her role in the development of The 1619 Project.

Published by The New York Times in 2019, The 1619 Project’s long-form journalism re-examines the legacy of chattel slavery, documenting its earliest moments and how free slave labor built the United States. In 2020, the New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute named The 1619 Project as one of the previous decade’s ten greatest works of journalism.

Despite its accolades, there is a nationwide effort to suppress the inclusion of The 1619 Project in school curricula, perpetuating what author Ta-Nehisi Coates recently referred to as the ”national myth that remade pirates into patriots.”

It’s almost as if history is repeating itself.

Learn more about the Wilmington Coup of 1898:

1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report by the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission

The Election of 1898 in North Carolina: An Introduction, University of North Carolina Libraries

Wilmington Massacre and Coup d'état of 1898 - Timeline of Events

Democracy Betrayed: The WilmiD.Don Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy

Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy, by David Zuccino

[VIDEO]Conversation with David Zucchino on the Wilmington Coup: NC Policywatch, May 2021

https://www.capefeargardenclub.org/ seems quite sinister now.