The Boys of My Summers

Reggie Jackson’s interview brought back memories of hot Arkansas summers, baseball, and racism

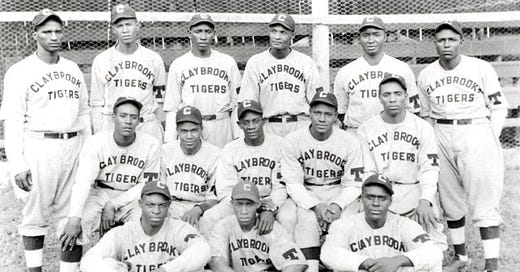

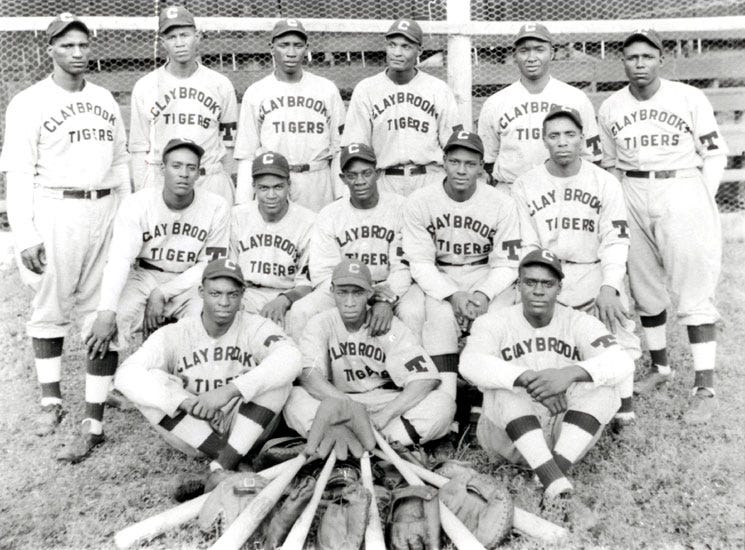

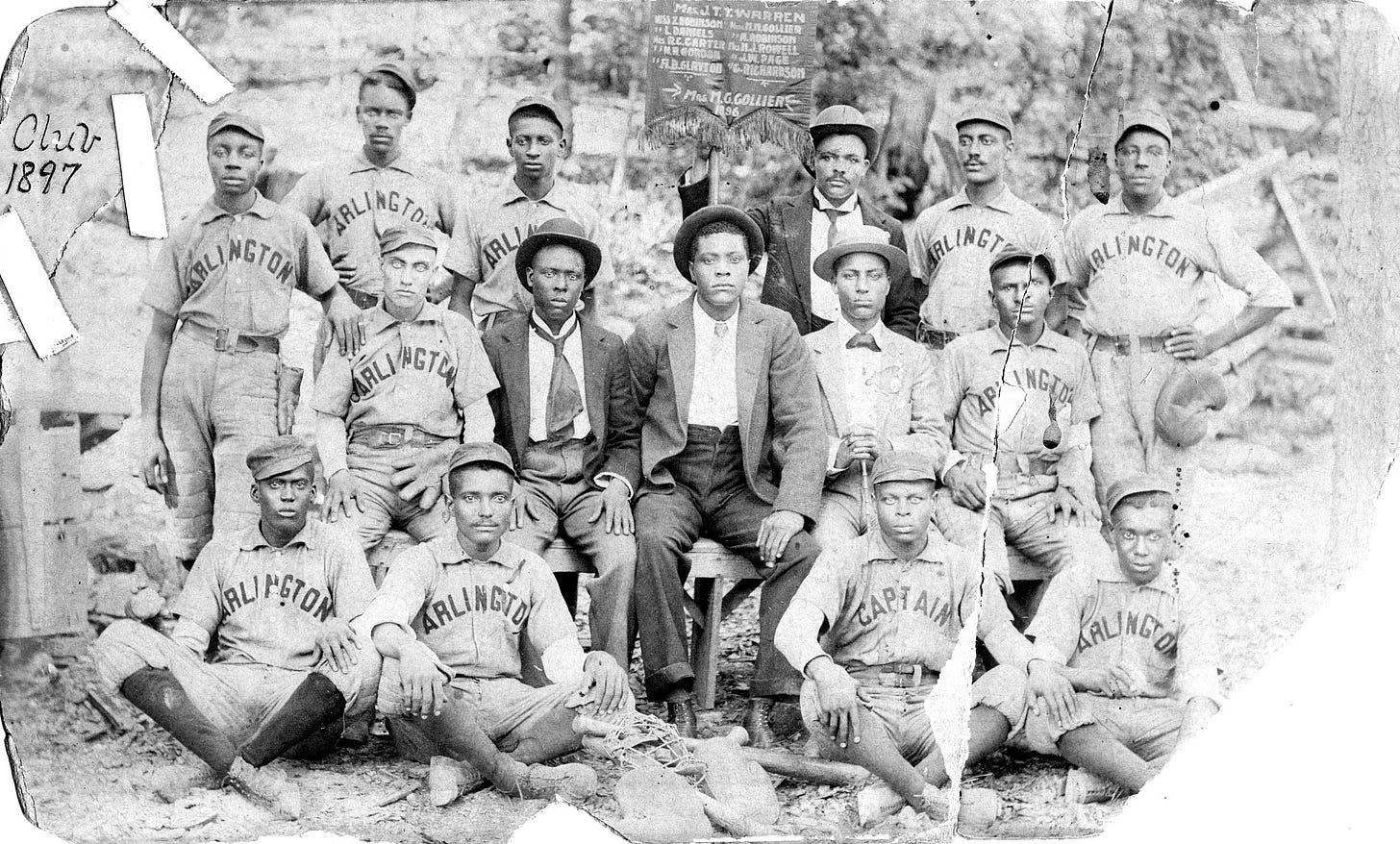

Last December, Major League Baseball announced that it would officially elevate Negro League baseball to “Major League” status. The move incorporates the records and statistics of the thousands of Black athletes who played in the Jim Crow-era league.

Over the weekend, I posted New York Yankee slugger Reggie Jackson’s interview during the pregame show for major league baseball’s tribute to Negro League baseball. The game also honored the late Willie Mays, one of the greatest players in MLB history, at Rockwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama. Mays had originally planned to attend but canceled a few days before he passed away.

Jackson, who played minor league ball at Rockwood in the late sixties, was asked by fellow ex-Yankee Alex Rodriguez how it felt to return to the Alabama ballpark. Jackson did not hold back.

For the next several minutes, baseball’s Mr. October recounted his experience as a young Black man in the Jim Crow South. Jackson shared the threats he received. He told of how he was repeatedly called the n-word while playing at Rockwood.

As Jackson told his story, you could hear the raw emotion in his voice. The scene was a dramatic departure from the scripted programming we've come to expect from network television. It was also a stark example of how even one of baseball's greatest players was not exempt from racism.

When I heard Jackson tell his story, I was reminded of moving to Pine Bluff, Arkansas in the early seventies.

In many ways the hour-long drive south from the state’s capital was like a trip back in time. In retrospect, most of the racism I experienced during childhood occurred in the Jefferson County town.

The town’s entire social order was built around the last vestiges of Jim Crow. While in Little Rock, we frequented Little Rock’s Pennick Boys Club, which was integrated. In Pine Bluff, however, the Boys Clubs were segregated by race—as was the city’s country club. There were still shop owners who avoided serving Black customers.

The most striking aspect of the town's racial hierarchy was its acceptance by the Black population. There were no riots, no uprisings. Although it was the seventies, Black folks acted as though all this was normal.

Jackson’s interview took me back to the summer days of my childhood, a time filled with sandlot baseball. The kids in my Black neighborhood played baseball across from my home, on a vacant field adjacent to the headquarters of the Pine Bluff Commercial newspaper.

Broken bricks marked the bases of our makeshift baseball diamond, a flat rock was our home plate. A ball hit over the railroad tracks that divided Fourth Street constituted a home run.

On the town’s sweltering summer nights my brothers and I made the short walk down Oak Street to watch adolescent white boys play Little League baseball. The reflection of the field’s floodlights against the night sky was powerful enough to see from our home. That, plus the booming echo of the league announcer’s voice was our signal that a game was in the offing.

Their baseball field, just a few blocks from my high school, was nothing like the unkempt lot where we played. We watched through the chain-linked fence surrounding it as teams of boys took the field. Sometimes we even saw our white classmates.

Under lights that transformed the night into day, my brothers and I admired the crisp, colorful uniforms of the players. We marveled at the manicured astroturf field, its chalk markings, the neat mound of fresh dirt prepared for the pitchers. Although we knew we could never play there, I don’t recall being angry. Like other Black children in Pine Bluff, I accepted the town’s racism as part of life.

Reggie Jackson’s story underscores how institutionalized racism is not something from the country’s distant past. It reminds us that there are people alive today who experienced Jim Crow racism firsthand.

It also reminded me that I am one of them.

.