The Badass Black Attorney You Didn’t Learn About in School

Turn-of-the-century lawyer Scipio A. Jones defied the odds in the Jim Crow south

Publisher's note: To make upgrading to a paid subscription more attractive to those who would like to support this newsletter, I've reduced the price by 40%, from $50 annually to $30, and from $5 monthly to just $3. This is not a sale that expires in a year. Your price will be the same for as long as you're a paid subscriber. ~MSW

I’ve written in the past about Minnie Muldrow Johnson, my mother’s sister, and how she overcame Jim Crow segregation to become one of the first Black women to receive a master’s degree at the University of Arkansas. During a career as an educator that spanned decades, she was also one of Arkansas’s first African American principals of an integrated school.

While remarkable, those achievements are only part of my aunt’s story. She and her husband Roger had a marriage that lasted more than fifty years. But perhaps the most beautiful aspect of their story is the way the two met.

During the Korean War, my Uncle Roger was a cook in a segregated unit of the U.S. Marines. It is unclear whether he was drafted or, as many young men did, he faked his age to serve in the war. Whatever the case, upon returning from his tour, he was eager to complete the final year of his high school education.

In an oddity of wartime, Minnie Muldrow, who was a recent college graduate about his same age, became his twelfth-grade teacher. The school where the pair met was North Little Rock, Arkansas's Scipio A. Jones High School.

Jones High School was founded as the Argenta Colored School in 1909 (North Little Rock was known as Argenta until 1917). The school changed its name to Hickory Street High School a few years later, then settled on its final name in 1928.

Until the mid-sixties, most of my extended family lived in the all-Black neighborhood surrounding Jones High School. While I knew about Jones High School as a youngster, no one in my family bothered to educate me on the significance of its namesake. I certainly didn't learn about him in school.

According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, Jones was born in 1863 in the town of Tulip, Arkansas. His enslaved mother, who was bequeathed to the man generally considered to be Jones’s father, was only fifteen years old at the time of his birth. Considering Arkansas’s racial climate from the end of the Civil War to the turn of the twentieth century, Scipio A. Jones compiled an astonishing record of achievement.

After the Civil War, Jones attended Walden Seminary (now known as Philander Smith University) in Little Rock. After graduating from the four-year school in only three years, he attended North Little Rock‘s Bethel Institute (now Shorter College), receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1885.

Jones studied law while teaching school full-time, passing the Arkansas bar in 1889. Jones’s credentials as an attorney were accepted by the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1900 and the U.S. Supreme Court in 1905.

What’s in a name?

Decades after I left Arkansas, a scene in Ridley Scott’s 2000 epic, Gladiator reminded me of Scipio A. Jones High School. One of the film’s colosseum scenes depicts a brutal reenactment of Rome’s victory in the Second Punic War over Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general.

The Roman general who orchestrated Hannibal’s defeat? Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus.

“Africanus,” the honorific bestowed upon Rome’s victorious general, means “the African” literally, but in the parlance of Ancient Rome, the addition to his name recognized Scipio as the conqueror of the entire continent of Africa.

Why, would Scipio Africanus Jones, a Black Arkansas lawyer, be given a name associated with an ancient Roman general? Historians have a theory for why so many of the enslaved were named after figures from Greco-Roman culture (emphasis added):

[G]iving enslaved people names of Western gods, goddesses, and heroes was done in sarcasm and irony, highlighting the contrast between the enslaved and their vaunted namesakes. For instance, Scipio Africanus was the famous Roman General who conquered Carthage in North Africa. By naming an enslaved man Scipio, his enslaver could emphasize even historical dominance of the African continent.

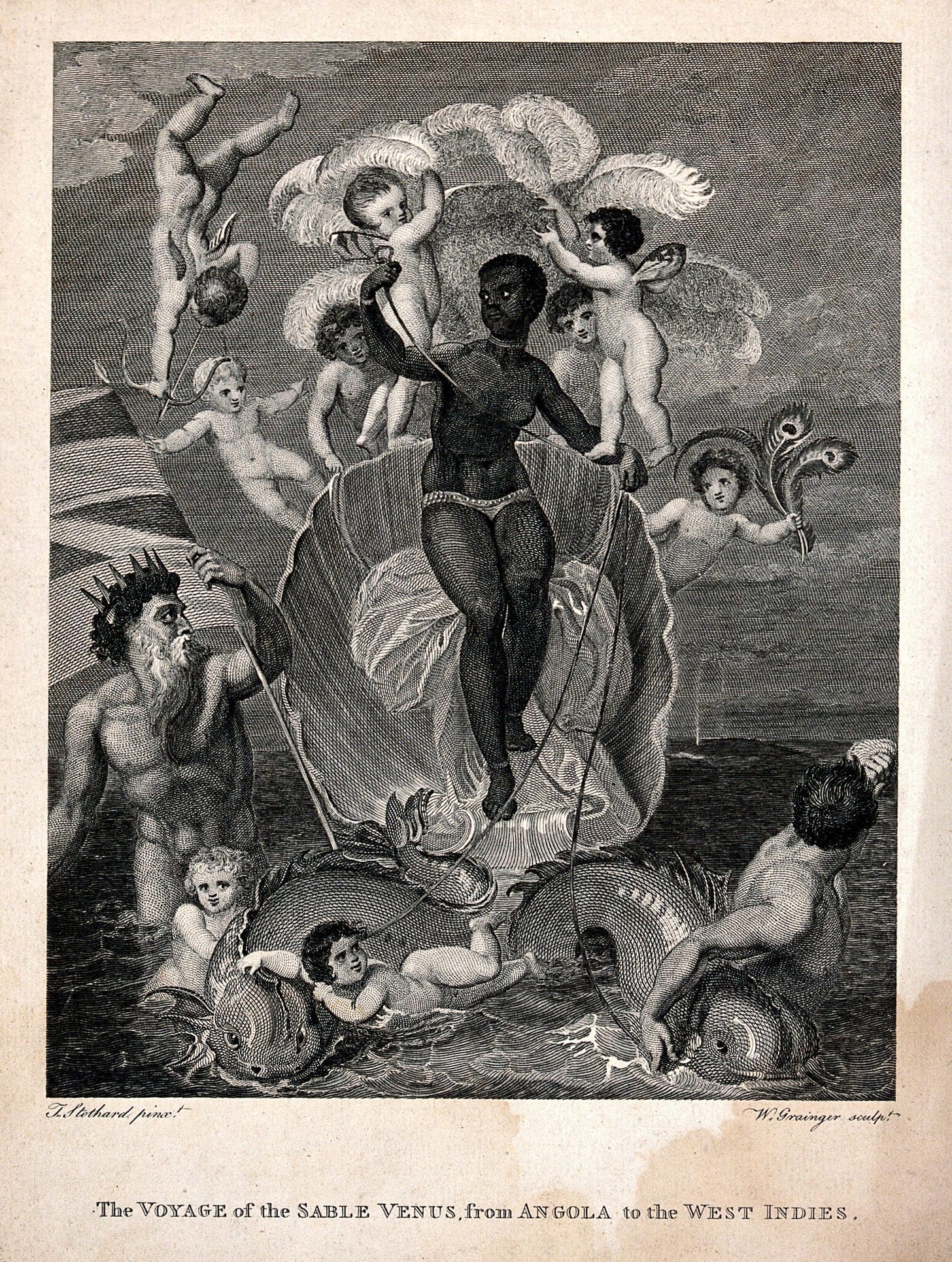

Additionally, some Classical names were meant to convey characteristics, especially for women. The name Venus, in particular, [Venus is believed to be the name of enslaved poet Phyllis Wheatley’s sister] was designed to assign sexual availability to enslaved women, who were often the targets of sexual violence. Naming an enslaved woman “Venus” after the Roman goddess of love and sex helped an enslaver justify his behavior to himself and his peers.

According to research by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, the name Scipio was such a common name for enslaved males, Harriet Beecher Stowe used the name for a protagonist in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Although I’d discovered the cruel intent embedded in Jones‘s name, it would be years before I fully understood the true reason he deserved the honor of having a school named after him.

The case that made Scipio Africanus Jones famous

Not long ago, my research on the Red Summer of 1919 led me to that year’s racist massacre in Elaine, Arkansas. As with most anti-Black violence throughout American history, the victims of the Elaine massacre were blamed for the attacks. Dozens of Black men were charged and imprisoned on charges in cases where the verdict was a foregone conclusion.

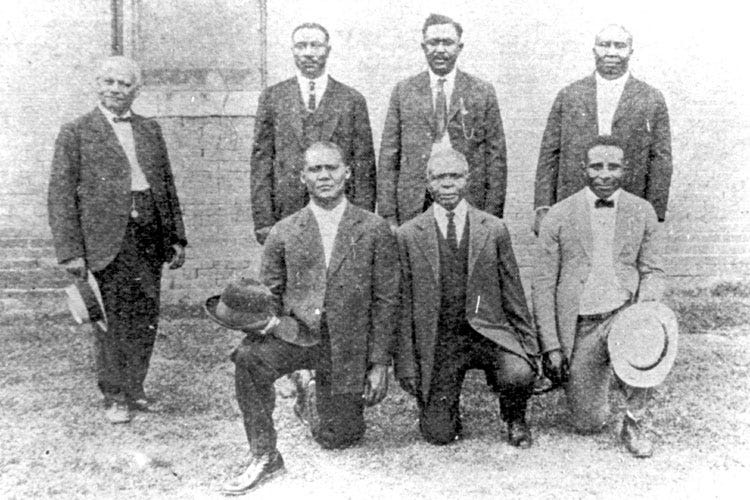

As I poured over photographs from the days following the massacre, there he was—the namesake of the school where my aunt and uncle met. By 1919, Scipio Africanus Jones, a man born a slave, was Arkansas’s most prominent Black attorney.

After the massacre, Jones was part of the legal team for a group facing the death penalty, known to history as the Elaine Twelve. Through a series of appeals and challenges lasting years, their case made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court (emphasis added):

The most significant case in which Jones was involved…was the defense of twelve Black men arrested during the Elaine Massacre. Between November 3 and 17, 1919, twelve men were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for murder in their roles in a supposed Black uprising; the trials were marked by weak evidence, a lack of cross-examination of witnesses, and short deliberations by the local juries. Jones was hired by African-American citizens of Little Rock on November 24, 1919, to work with the firm of George W. Murphy, an attorney hired by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to defend the twelve condemned men. By January 14, 1925, all twelve defendants had been released.

Prior to his death in 1943, Jones represented the indigent, twice served in a temporary capacity as a judge, and in 1924 was elected as a special chancellor in Pulaski County Chancery Court. In 2022, Jones was inducted into the Arkansas Bar Association Legal Hall of Fame.

Desegregation of North Little Rock public schools resulted in Scipio Jones High School’s closure in 1970. The neighborhood where my grandparents, aunts, and uncles once lived has vanished, decimated by 1960s urban renewal.

My Aunt Minnie and Uncle Roger have long since passed away. But as fate would have it, the home they lived in for decades still stands. If you're ever in North Little Rock, Arkansas, it's not that hard to find.

It is located at the intersection of Scipio Africanus Jones Drive and Vine Street, a few blocks away from the spot where they met and fell in love.

Further reading:

Encyclopedia of Arkansas: Elaine Massacre of 1919

Scipio A. Jones High School National Alumni Association

I don’t work in the fields you do, but there’s a few similar(ish) stories in the nuclear field. My personal favorite story is that of J Ernest Wilkins Jr who was not allowed to work at X10 (now the Oak Ridge National Laboratory) during the Manhattan project due to Tennessee’s Jim Crowe laws. This was despite getting a personal recommendation from Edward Teller! He worked up in Chicago and created some of the fundamental reactor physics for plutonium productions then and reactor physics generally. Among a list of other accomplishments he’d serve as the president of the American Nuclear Society in the 70s. It’s a story I wish I knew sooner. Thanks for this read about another figure I never knew about!

An incredible read... makes me very proud as a human being to know of this intense quality of character and ability to rise up and overcome horrible adversity. And it grinds my gears too because I read this in a time where lawmakers are actively engaged in erasure efforts to squelch information like this lest it support Black pride and intimidate fragile white mythology. Thank you for sharing this wonderful story of these treasured Americans, and the links afterwards are terrific too.