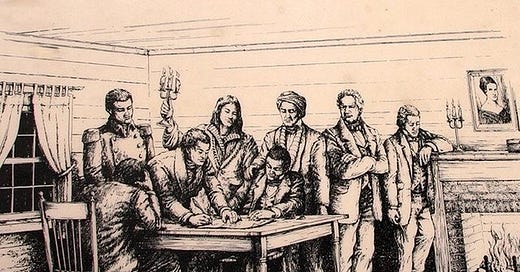

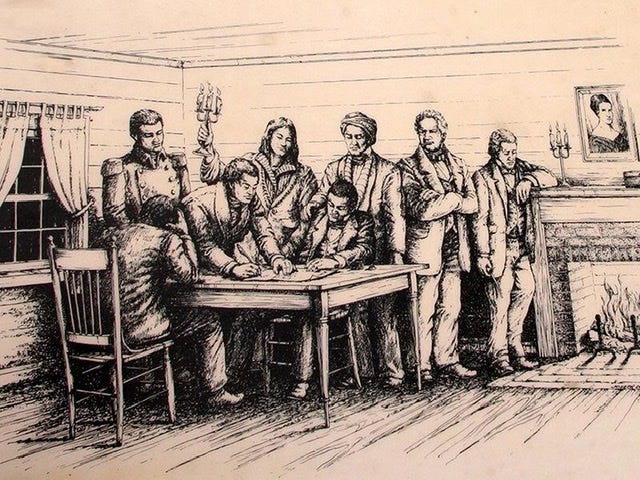

How Becoming “Civilized” Ended with the Trail of Tears

The portrayal of Native Americans in popular culture often overlooks a complex history that included slavery

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Journeyman. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.