A Secret Holocaust of My Childhood: The Wrightsville Fire of 1959

For decades, the tragic story of the Arkansas Boys Industrial School was part of the state's hidden history

Note: As most of you know, February is Black History Month in the U.S. With that in mind, I decided to focus this month’s posts on hidden Black history—the lesser-known stories we don’t typically hear about in media. This post focuses on a dark episode in my home state’s history and its relation to my childhood. ~MSW

History is fascinating. It is a work in progress. It evolves. Many times, the history we think we know is but a fable. But every so often, long-hidden history, not to be ignored, reaches out from the depths of obscurity, extending its hand from the distant past to tap us on the shoulder.

This is the story of one of those times.

My three brothers and I spent our pre-teen years in Little Rock, Arkansas. From that time, my fondest memory is of living in a one-story, three-bedroom house on Marshall Street in a mostly Black neighborhood filled with children.

Our parents both held full-time jobs, so we spent a good deal of time left to our own devices. We played four-square and hide-and-seek for hours on end. We played baseball and touch football in the middle of Marshall Street without worry. It was a time devoid of video games and free of social media.

Except for Mrs. Pearl, the rotund, elderly white lady who paid me five dollars a week to mow her dangerously sloped yard, my childhood neighborhood was as segregated as my elementary school.

During my time on Marshall Street, the number of boys in the neighborhood became fewer, decreasing one by one. At the time, I assumed some moved away, as we did years later. However, there were times when I wondered if the boys in my neighborhood met a more sinister fate.

Once, I recall seeing on the local news that a boy my age was a suspect in a neighborhood grocery store robbery. Days later, police captured the young suspect, hiding between the mattresses in his bedroom.

News crews broadcast the scene of police escorting a disheveled young Black kid to their vehicle. To my horror, it was Bobby P., a boy I’d played with for days on end in the hot Arkansas summers, who’d eaten at our dinner table, a boy I considered a friend. After that news story, I never saw Bobby again.

Unlike Bobby, my three brothers and I were what one might call ‘good boys.’ We rarely broke our parent’s rules and seldom got into trouble at school. Beyond the twin threats of our six-foot-five father and our mother, with her creative methods of administering corporal punishment, there was another reason we kept to the straight and narrow:

We were deathly afraid of being sent to the Boys Industrial School.

On the occasions when we stepped out of line, my mother would drive us to the Stifft Station area of Little Rock, directing our attention to an ominous group of buildings set far back from the road. A towering wrought iron arch rose over the entrance, adding to the area’s atmosphere of foreboding. To my brothers and me, this appeared to be some kind of asylum. Whatever this place was, it was totally out of place in this otherwise upscale part of the city.

“That is the Boys Industrial School,” she would tell us, with a serious expression, “That is where bad boys go to live.”

In the early 1970s, our family moved away from Little Rock. I soon forgot about Marshall Street, Bobby Phillips, and the looming threat of the Boy’s Industrial School. Years later, I returned to the city of my childhood, married, and soon had children of my own. On my way to work each morning, I drove past the towny area of Stifft Station. Once a source of childhood anxiety, the school's ominous buildings were now a source of nostalgia.

As I drove by each morning, I looked fondly upon the campus of buildings, recognizing in adulthood that, according to the arched wrought iron span that graced its entrance, this locale was not a destination for juvenile delinquents. This conglomeration of buildings was, in reality, the Arkansas School for the Deaf and Blind.

At the time, I assumed the idea of a school for unruly juveniles was a parental invention — a fictional device to keep us in line. In the years that followed, the mythical school “where bad boys go to live” became part of my family’s story, a humorous footnote in my childhood narrative. And there it remained until a few weeks ago when my oldest living relative passed away.

Reading my Cousin Justine’s obituary, a brief chronicle of a life well-lived, I noticed, to my surprise, the centenarian was once an employee of the same school for disabled children that was the physical manifestation of my parent’s fable all those years ago. I laughed aloud as I recalled the story from my childhood.

“So Cousin Justine worked at the Boys Industrial School,” I wrote in a text to my only brother still living in Arkansas. His return text met my attempt at humor with a somber reply:

“That school was actually in Wrightsville, and it had a tragic history.”

The smile evaporated from my lips, replaced with a silent gasp. I spent the next hour reading the horrific story attached to my brother’s text message, spellbound in disbelief.

The Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School, or NBIS, was a segregated juvenile correctional facility and work farm for black youths. Established in 1923, the school had two different locations, first in Jefferson County, just outside of Pine Bluff, then from the 1930s on in Wrightsville, then an unincorporated hamlet about 13 miles southeast of Little Rock, Arkansas.

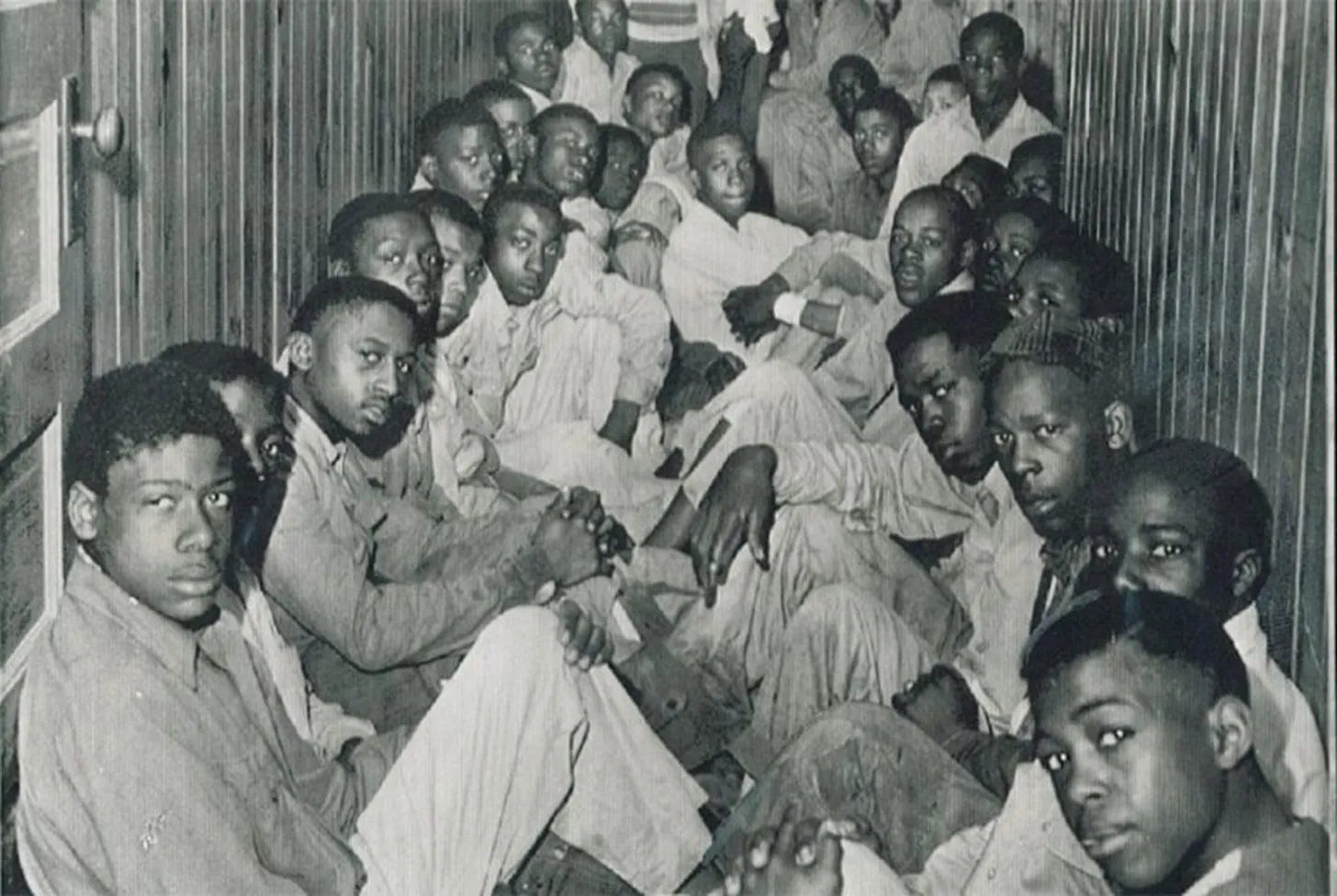

The youth dormitory was a dilapidated Works Progress Administration building, a relic of the New Deal era, constructed in 1936. The building sometimes housed as many as 100 children between 13 and 17 in a dormitory with beds barely a foot apart.

Authorities committed Black orphans to the NBIS work farm as well as homeless children. They incarcerated teenagers for petty offenses, such as “mischief” or hubcap stealing. In one instance, authorities imprisoned a boy for the Halloween prank of “soaping windows.”

In 1956, sociologist Gordon Morgan, who would go on to become the first Black tenured professor at the University of Arkansas (full disclosure, Professor Morgan was my sociology instructor at the U of A), wrote his Master’s thesis on the school, documenting the stunning level of squalor at the Wrightsville facility:

“Many boys go for days with only rags for clothes. More than half of them wear neither socks nor underwear during [the winter] of 1955–56….[It is] not uncommon to see youths going for weeks without bathing or changing clothes.” At times, the number of boys at the “school” was over 100. There was no laundry equipment. A single thirty-gallon hot water tank served the bathing needs of the entire population. The water was deemed undrinkable. Employees brought their own drinking water to work.”

In contrast to the appalling conditions of the NBIS, the State’s trade schools for white adolescents emphasized the depths of Arkansas’ institutional racism. The white schools prepared inhabitants for various vocations; teaching carpentry, cabinetwork, and bricklaying. One of the reform schools for white boys made 156 mattresses for beds at the Wrightsville facility.

In theory, the NBIS provided agricultural training to Black juvenile delinquents as a prison alternative as its primary mission. The facility was a working cotton farm, with a dormitory located on the NBIS working cotton farm. However, in practice, the facility was little more than a penal work farm for incarcerated Black teenagers.

The existence of an institution of its kind is a reminder of the South’s Jim Crow era of segregation. The harsh, prison-like conditions made the NBIS a school in name only. At one point during its existence, armed overseers monitored the boys as they worked the cotton fields. Supervisors reportedly disciplined older boys with severe whippings.

At around 4:00 a.m. on a cold, wet morning in March 1959, twenty-one Black teenage boys burned to death inside the Negro Boys Industrial School's dormitory.

The night of the fire, padlocks secured the entrance to the dormitory from the outside. No adult supervisor was on duty, leaving the young boys trapped in their cramped sleeping quarters. That same night near Pine Bluff, an institution for white juvenile offenders had two adults on duty, with the entrance to the sleeping quarters unlocked.

The forty-eight survivors of the NBIS inferno made their escape by clawing their way through the mesh screens protecting the dormitory’s windows. When fire trucks reached the scene, they found the charred remains of twenty-one children piled atop one another in the corner of the dormitory’s sleeping area.

The Wrightsville incident drew worldwide attention, appearing in newspapers across the country, including the New York Times. Orval Faubus, the Arkansas governor and staunch segregationist, who just a few years earlier gained notoriety in the Little Rock Central High desegregation crisis, moved quickly to take control of the tragedy’s narrative.

The Governor immediately called for a criminal investigation, seeking to lay blame for the incident on Lester R. Gaines, the Black superintendent and Faubus appointee.

Above: Interview with Roy Davis, a survivor of the Negro Boys Industrial School fire of 1959. Davis died in prison in 2020 from complications of Covid-19. Sources: YouTube, Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette

The exact cause of the fire remains shrouded in mystery. Police did none of the routine investigatory procedures, such as determining the fire's cause or preserving the incident scene.

A grand jury concluded the correctional facility, the State of Arkansas, and the state legislature held responsibility for the incident but returned no indictments.

In the end, no one was held responsible for the fire. The NBIS board of directors recommended a “severe reprimand” for the employee scheduled to work that fateful night. In the end, no one was held criminally responsible for the fire, and the board terminated Gaines, his wife, and one other school employee.

The families of seven of the boys arranged for private funerals. The remaining fourteen boys' bodies were wrapped in newspaper and buried in an unmarked mass grave at Haven of Rest, a Little Rock cemetery.

The State of Arkansas awarded each of the boy’s families between $3,300 and $5,900 in damages for their losses; however, white attorneys representing the families took as much as half that sum in compensation. One family reported receiving only $1,400. The rising Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and the resistance to it by Arkansas’ white supremacist establishment overshadowed the incident.

Over the next sixty years, the story of one of the worst tragedies in Arkansas history faded from consciousness. The world forgot the story of the Wrightsville 21 and the Negro Boys Industrial School.

More than five decades later, no plaques, no monuments, not even a marker of the mass gravesite existed to commemorate the lives of the boys who perished in 1959. By then, the notion of a place “where bad boys go to live” became little more than a fantastical tale, an urban legend used by Black parents — like mine — to frighten their unruly children into good behavior.

But as history tells us, nothing stays hidden forever. At the urging of surviving family members, the Little Rock media revisited the Wrightsville tragedy in the early 2000s. In 2017, KATV, a local television station, ran a feature questioning the fire’s cause.

Several books published that same year brought renewed interest in the tragedy. In 2019, CNN’s Don Lemon retold the Negro Boys Industrial School story, hosting Up From the Grave: Arkansas’ Deadliest Fire, a four-part podcast. In 2020, Death by Design: The Secret Holocaust of Wrightsville, Arkansas, a play about the deadly fire, debuted at Little Rock’s Mosaic Templars Cultural Center.

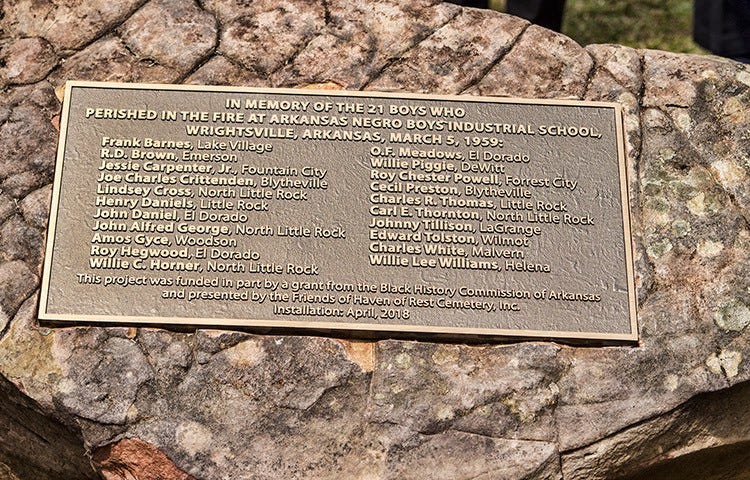

Today, visitors to the Haven of Rest Cemetery will find a memorial plaque listing the names of twenty-one Black boys who died in the fire at the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School. In 2019, government officials placed a monument on the land where the school for Arkansas’ most unfortunate Black boys once sat, in an unincorporated hamlet, about a mile down a dirt road.

In perhaps the bitterest of ironies, that spot is also the current location of the Wrightsville unit of the Arkansas Department of Corrections — a state prison.

If you enjoy and would like to support The Journeyman, please consider signing up for my weekly-ish newsletter. You’ll receive early access to my posts, subscriber-only podcast, and occasional Zoom events.

Another tragedy today in 2022 in Chicago children of color in foster care are housed in psychiatric and juvenile detention centers. The director of Department of Children Family (Mr. Evans) Services has been held in contempt of court order for leaving children in these facilities for more than 30 day